3 Steps to Break out of Your Mental Sand Traps

Improve your decision-making and avoid three mental hazards.

Photo by Tim Johnson on Unsplash

Have you ever been stuck at a decision point, trapped in uncertainty or paralysis? Or have you had the experience of making a poor decision? It would be hard to find someone who doesn’t relate to one or the other. Ready to make this year full of great decisions? First, consider how you make decisions.

You can choose a ready guide in some celestial voice

If you choose not to decide, you still have made a choice

You can choose from phantom fears and kindness that can kill

I will choose a path that’s clear, I will choose free will

Those are the lyrics to “Free Will” by drummer Neil Peart of the Canadian band Rush. Peart was highly perceptive about human behavior, as reflected in songs revealing numerous cultural, humanitarian, and philosophical themes. And, from the academic corner, Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman agrees with the talented drummer-songwriter. Based on Kahneman’s work in decision-making, we humans make poor decisions because we:

- Are overconfident (Peart calls this a celestial voice—a Higher Power, inner voice, or instincts)

- Cautious to a fault (choosing not to decide)

- Get caught up in emotions (phantom fears and kindness that can kill)

Sometimes, the reason behind an undesirable result in a decision can be traced back to insufficient data, poor alternatives, or misguided costs and benefits. But we can often trace poor decisions back to how our minds work.

Read on to learn how to recognize and escape three common thinking sand traps before they become judgment disasters.

Kahneman posits that we have two thinking systems. System One is unreachable; it’s our unconscious and fast reaction to things, often based on intuition. It cannot be turned off.

Our System One thinking is responsible for most of our daily decisions, judgments, and, surprisingly, many purchases. System Two thinking accesses working memory in the rational side of our brain, which helps us make more analytical and deliberate decisions, such as weighing our pros and cons.

Have you ever purchased a costly but unneeded item on the spur of the moment because you wanted it, then rationalized your decision on the ride home? That’s our System One and System Two thinking at work. System One makes a quick decision in the heat of the moment; System Two helps to make sense of more complex scenarios. Unfortunately, System Two thinking uses a lot of mental processing, which means it’s System One that is usually in charge. Therefore, our first instinct is often a poor first decision, especially if we are emotional, because of cognitive biases and built-in mental shortcuts.

There are many biases—the Decision Lab lists around ninety! Decision-making is big business, especially with the modern advantages of AI and innovations in data science. But let’s focus on individual decision-making and biases.

The good news is that sometimes a bias can be helpful to facilitate other life tasks. But, more than likely, our biases can become obstacles. Here are three prevalent decision-making biases and how they show up in our day-to-day decisions as helps or hazards, and a few responses to breaking out of the sand traps.

The Status-Quo Trap

The Bias: Decision-makers display a strong bias toward alternatives that keep things as they are. Studies show that when people are given one of two gifts and are told they can exchange it for the other, only one in ten do. The more choices we are given, the stronger the appeal of keeping the status quo.

What we do: Avoid taking actions that change the current state.

Why do we do it? To protect ourselves from risk. Loss aversion. Fear of failure. Feeling overwhelmed.

How it shows up in our day-to-day lives:

Why break free? So you don’t miss out on beneficial opportunities and advantages

3 acts to break free of this sand trap:

- Revisit the goal and examine if the status quo hurts or hinders it.

- Identify other options and consider the pros and cons

- Imagine a future where the status quo has changed and then evaluate the choices

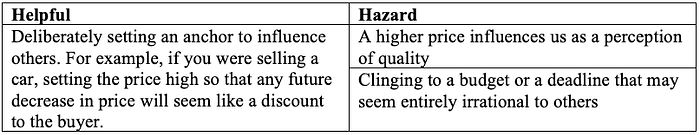

The Anchoring Trap

The Bias: A person relies too heavily on the first piece of information about a topic, becoming anchored by values that aren’t relevant to the topic. The anchoring bias has a powerful effect on human psychology and is highly pervasive in decision-making. In addition, anchoring can drive other cognitive biases, such as the planning fallacy (underestimating the amount of time it might take to do a task) and the spotlight effect (overestimating our significance to others or negatively exaggerating it.)

What we do: We filter information around a belief and then build a mental model consistent with that belief, even when evidence shows we are wrong. And the more we think about the scenario, the more we are anchored in our beliefs.

Why do we do it? We don’t want to admit we are wrong. We like consistency and patterns.

How it shows up in our day-to-day lives:

Why break free? So you can contribute to creating an inclusive, engaged, and diverse environment for solid decision-making.

3 acts to break free of this sand trap:

- Intentionally seek other points of view that challenge the anchor, essentially creating a counterargument

- Design short, safe-to-fail experiments to test new ideas

- Embrace a culture of learning and celebrate shared knowledge, especially when it is spawned by a failed experiment, to embrace the process

The Framing Trap

The Bias: The Framing Effect occurs when people decide something based on how information is presented instead of the information itself. In other words, the same facts presented in two ways can lead people to make different decisions. For example, agreeing to medical treatment with a 90% chance of survival is more appealing than hearing that the same treatment has a 10% chance of death. It’s the same data with different framing.

What we do: We instinctively avoid certain losses over an equivalent gain.

Why do we do it? We are wired to avoid loss, and many of us have an inherent aversion to risk.

How it shows up in our day-to-day lives:

Why break free? So we don’t undervalue facts or make decisions based on poor information

3 acts to break free of this sand trap:

- Don’t accept the first frame; draw out different aspects of the problem using multiple points of view from others not invested in the decision.

- Map out various choices with all the facts before making a decision.

- Consider how your decisions would change if the framing changed

Responding versus Reacting

Kahneman’s work notes that our first reaction is often poor, and biases are inherent in decision-making. In addition, in our current knowledge era, we must learn how to make adaptive decisions in the face of ambiguity. To make things more complex, we often make decisions as a group or system dynamic rather than individually. Dave Snowden, known for the Cynefin framework, describes this modern decision complexity with the delicious phrase “the science of inherent uncertainty.”

The steps to successful decision-making are:

- Build awareness of your biases and mental shortcuts.

- Learn to identify the complexity of the problem accurately.

- Follow through with subsequent action and adaptation.

As with everything else, decision-making is situational, and the sands of change shift arbitrarily. Therefore, how you make decisions, especially learning to adjust as situations evolve, will make the difference between reacting and responding.

Behavioral science is relatively new, but studying human behavior is not. It’s a fun fact to conclude with a note that Kahneman wrote his book, “Thinking, Fast and Slow” in 2011. Neil Peart wrote “Free Will” in 1980.

~Julee Everett

Hone your craft, speak your truth, show your thanks

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Visit Julee Everett’s YouTube Channel for a growing library of webinars and conference talks.

Sources you might find interesting related to behavioral science:

The book: “Thinking, Fast and Slow,” by Daniel Kahneman

The podcast “No Stupid Questions” by Stephen J. Dubner (co-author of the “Freakonomics” books) and research psychologist Angela Duckworth (author of “Grit”)

One of many valuable sites on the topic: https://thedecisionlab.com